“Le Palace is not a boîte, a "box" as we French call a night club: it collects in an original site pleasures ordinarily dispersed: that of the theatre as an edifice lovingly preserved, the pleasure of what is seen; the excitement of the Modern, the exploration of new visual sensations, due to new technologies; the delight of the dance, the charm of possible meetings. All this combined creates something very old, which is called la Fête and which is quite different from Amusement or Distraction: a whole apparatus of sensations destined to make people happy, for the interval of a night. What is new is this impression of synthesis, of totality, of complexity: I am in a place sufficient unto itself. It is by this supplement that Le Palace is not a simple enterprise but a work, and that those who conceived it may regard themselves with good reason as artists.”

Total art

In this article, Roland Barthes writes about how Le Palace, a Parisian night club in a former theatre, beguiles him.1 It's a theatre where you can circulate, you're not bound to an assigned seat. You walk from one familiar place to another: "a salon for chatting, bars to meet in, to rest in between dances, a belvedere from which to gaze, above the intervals of the balustrades, down at the immense spectacle of lights playing over bodies." Barthes calls the club a public art (achieved among the public and not in front of it) and a total art (the old Greek and Wagnerian dream), where scintillation, music, and desire unite.

1. Barthes, Roland. “At Le Palace Tonight”. Vogue Hommes, May 1978.

The whole article resonates very well with what I believe a club is. It can indeed be regarded as a democratic, total work of art when it's conceived as such. Barthes also relates it to theatre, mainly because of the preserved architectural elements and their (transformed) functions, as well as etymologically (théatron, "a place for viewing"), a club as a site dedicated to looking. I will take it a step further in the next chapter and consider a club night as a (directed) performative event in a theatrical and scenographic setting.2

2. Setting because it is not necessarily bound to a venue, it could also be at home or outdoors, though in this document I will concentrate on indoor clubs.

Although clubs exist much longer, think about ballrooms and jazz clubs, and club culture finding its roots in rituals performed in almost all ancient cultures, we could take the 1960s as a starting point of modern club culture. It is the moment where people start to dance on recorded music instead of live music, technology comes in (light effects and amplified sound); resulting in the so-called discotheques which became popular practically all over the world.

Pol Esteve describes in his article Total space how interconnected groups of promoters, architects and engineers developed a new kind of spatial experience.3 These projects explored new perceptual environments, which radically challenged the way spaces and clubs were thought about.

3. Esteve, Pol. “Total Space”. Night Fever, Designing Club Culture, 1960-Today, Vitra Design Museum, 2018, pp. 131-147.

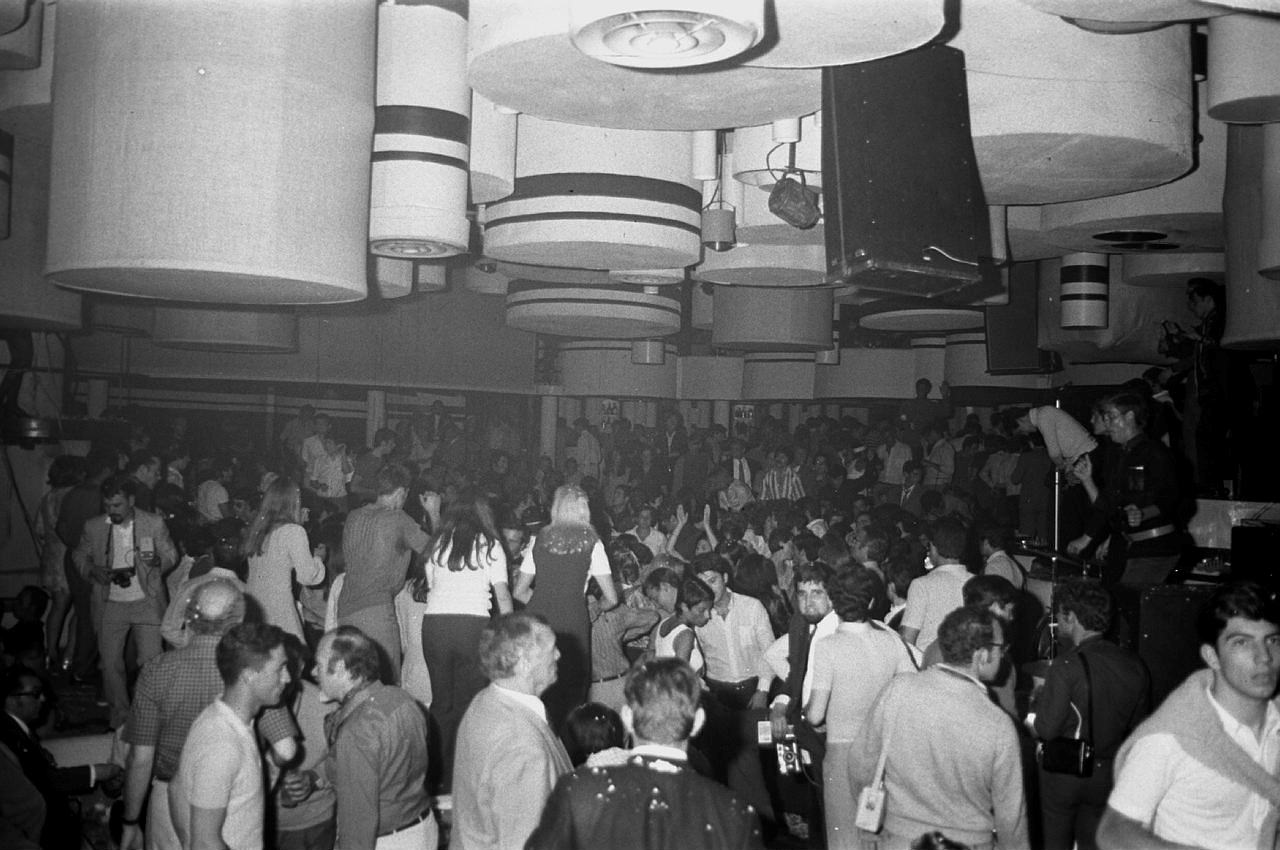

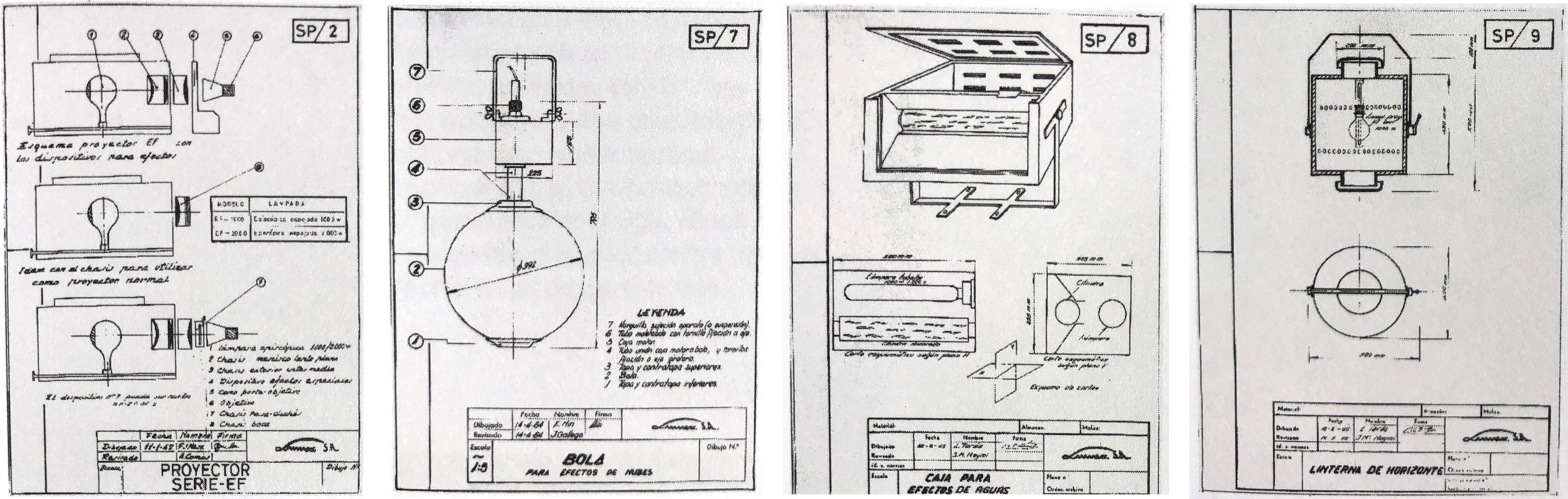

Maddox (1967-2005), for example, had an innovative multifunctional interior resembling a stalactites cave. The ceiling consisted of an accumulation of suspended cylindrical elements while a series of circles defined the seating areas with fixed circular sofas alongside circular stools which could be moved around freely. In the central hollow position, there was a relatively small circular surface for dancing. However, it was not the multifunctionality, the flamboyance of the interior nor the futuristic style that made Maddox an unprecedented kind of space. The element that made the space of Maddox unique at the time, and was virtually invisible in any documentation as it's near-impossible to capture in photography or film, was the design of the light and sound systems. Although these devices are ubiquitous today, they were not industrially produced at the time.

Episcope for Maddox, designed 1962. Projector to generate cloud effects, designed 1964. Projector to generate water effects, designed 1965. Horizon lamp, designed 1965.

Light fixtures and instruments were custom designed and inspired by devices used in theatres and dioramas. Other effects came directly from the scientific field: stroboscopes, UV lamps and lasers. They render an aesthetical sophistication while still maintaining an experimental look when we compare it to the off-the-shelf lighting instruments we have today. The design process itself forces deliberate artistic decisions to be made, instead of choosing a fixture or effect from available options.

DJ booth "table of the operator". Photograph: Photo-Flash, 1973.

The sound system consisted of suspended loudspeakers above the dance floor, distributed speakers around the space and subwoofers (the first patent for this type of loudspeaker was granted three years earlier). The "table of the operator"4 consisted of two turntables used in parallel to play songs without interruption and a reel-to-reel tape machines. The booth did not only contain the mechanisms for playing music but for controlling the lighting as well. In this way, the operator could regulate the atmosphere. As such, the light and sound operators were the designers of a new spatial experience, that challenged the modern conception of space in the architectural realm.

4. Carmenati, one of the architects, uses this term.

Dancing bodies and projections in Maddox, 1968.

Dancing bodies and projections in Maddox, 1968.Esteve uncovered a third "micro-technology" crucial to the production of the spatial experience. It was not part of the design and could not be controlled from the "table of the operator", and is chemical in nature: psychoactive substances or —to use a more common word with an often negative connotation— drugs. Back then, mescaline and LSD (hallucinogens), as well as amphetamines, were legally available in Spain. These substances intensified the experience of the space itself, as well as the effects of the light and sound technologies. The designers of these technologies (and probably the operators too) were very aware of the impact and used it deliberately. Maddox was described as a psychedelic space in multiple press reviews. This condition makes the experience highly individual and subjective: the spatial experience is not predesigned by the architects and engineers but is created within the bodies and minds of the clubgoers.

A club as a community

If we look at the previous examples, we see a lot of effort into the design and creation of these new spatial environments. These examples are high profile clubs. They are heavily designed, both architecturally and technologically and have enough resources for these new technologies. However, a club is also a place to meet other people, a social space that doesn't necessarily need a sleek design or state-of-the-art technology as we see in the next cases.

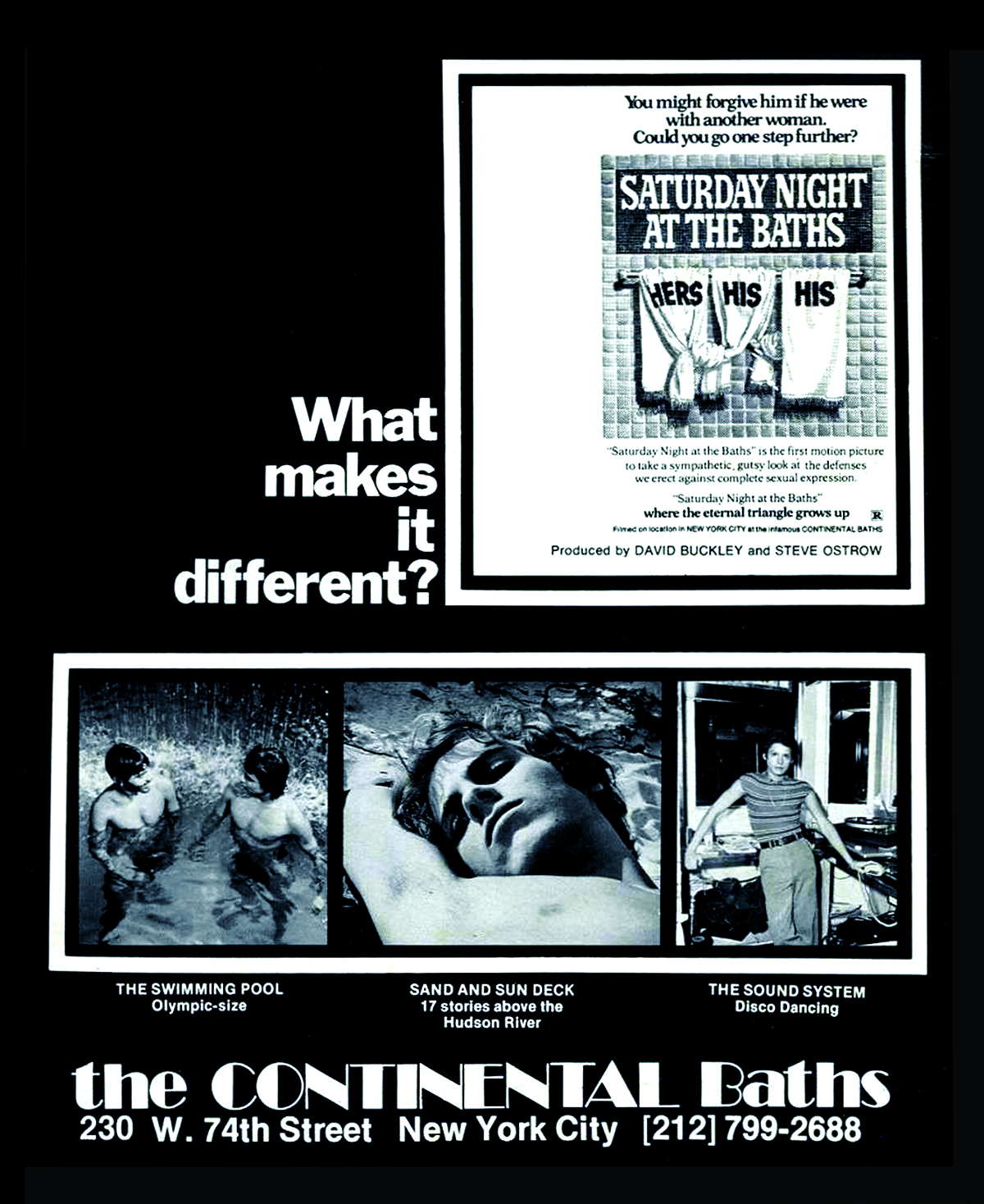

In 1968, Steve Ostrow opened the Continental Baths in New York. The bathhouse was a social space where gay men could meet, socialise, swim, relax and have sex. When the popularity grew, Ostrow began booking entertainment. "I built a disco room, a DJ booth, and these special things where you put the records: 'turntables'!"5 Over the eight years of its existence, it became a cultural hub for music, clubbing and queer culture, providing gay men with a safe space6, unlike anything that had been seen before.

The Baths also acted as a safe space to develop the talent and launch many successful careers of performers and DJs. It became a disco incubator that helped produce the birth of two of the most famous DJs in history: Larry Levan and Frankie Knuckles. These two African-American friends were under 21 when they "spent many hours, days, and nights playing one-for-one, honing and sharpening [their] skills". By the end of 1974, Larry Levan had outgrown the Continental Baths and their unadvanced sound system. He became a resident DJ at SoHo Place, a loft space of sound engineer Richard Long. Later he found his permanent home at The Paradise Garage, which became one of the most legendary clubs in history thanks to Levan's otherworldly control of the devoted crowd from the black and Latino queer community. Knuckles moved to Chicago and its black Latino gay club The Warehouse. A venue where he began to experiment with editing disco breaks on a reel-to-reel recorder, reworking and recombining the raw material that would soon evolve into house music.

The Baths also acted as a safe space to develop the talent and launch many successful careers of performers and DJs. It became a disco incubator that helped produce the birth of two of the most famous DJs in history: Larry Levan and Frankie Knuckles. These two African-American friends were under 21 when they "spent many hours, days, and nights playing one-for-one, honing and sharpening [their] skills". By the end of 1974, Larry Levan had outgrown the Continental Baths and their unadvanced sound system. He became a resident DJ at SoHo Place, a loft space of sound engineer Richard Long. Later he found his permanent home at The Paradise Garage, which became one of the most legendary clubs in history thanks to Levan's otherworldly control of the devoted crowd from the black and Latino queer community. Knuckles moved to Chicago and its black Latino gay club The Warehouse. A venue where he began to experiment with editing disco breaks on a reel-to-reel recorder, reworking and recombining the raw material that would soon evolve into house music.

5. Davis, Sam. “Sex, disco and fish on acid: how Continental Baths became the world’s most influential gay club”. The Guardian, 27 April 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2018/apr/27/sex-disco-and-fish-on-acid-how-continental-baths-became-the-worlds-most-influential-gay-club

6. Nevertheless, Ostrow estimated that the police raided the place over 200 times as homosexuality was illegal in New York at that time.

6. Nevertheless, Ostrow estimated that the police raided the place over 200 times as homosexuality was illegal in New York at that time.

House, the kind of music you'd hear at The Warehouse, wasn't born as a distinct genre but "as an approach to making 'dead' music come alive, by cut' n' mix, segue, montage and other DJ tricks. Just as the term disco derived from the discotheque, so house began as a disk-jockey culture".7

7. Reynolds, Simon. Energy Flash : A Journey Through Rave Music and Dance Culture. Faber and Faber Ltd, 2013, pp. 20-21.

The music aesthetics, which were not yet clearly defined in the late 60s and the early 70s, were developed over time within the club community. This shows that we shouldn't consider club culture as a series of individual events or independent spaces, but as a network of communities in which the aesthetics and practices are born, evolve and spread. Until today, house and techno are the dominant genres defining the music aesthetics in club culture.

Disco-aesthetics becoming mainstream

Discotheques spread quickly around the world. Most of them functioned rather like bars laced with disco-aesthetics instead of being community spaces where artistic and technical development takes place. At that time, going to a discotheque was merely a form of entertainment. The spaces and the behaviour of participants increasingly conformed to social norms turning the clock back to the pre-discotheque era.

Deller, Jeremy. Everybody In The Place : An Incomplete History of Britain 1984-1992. 2018.

However, with his documentary Everybody In The Place - An Incomplete History of Britain 1984-1992, Jeremy Deller upturns popular notions of rave and acid house, situating them at the very centre of the seismic social changes that reshaped the 80s. He shows how club culture emerged from the black communities around Britain, resulting in raves and parties which crossed previously impregnable boundaries of class, identity and geography.

In Belgium, a new scene arose from the development in music aesthetics. Influenced by the Chicago-originated acid and house music and the dark Belgian industrial and new wave from earlier in the 80s, a new danceable genre was born: the New Beat. The Boccaccio became its "holy temple". Together with similar clubs and after-clubs, it gathered thousands of people each weekend. Unsurprisingly these parties and raves came, like their British counterparts, in the crosshair of the police and the mainstream media, wherein they were often demonised. As a consequence, all those venues were forced to close their doors by the local governments. Until today club culture keeps up the tension with conservative public opinions and politics as well with authorities, making exercising club culture tough due to complicated licences, rules and ambiguous drug policies, especially for small scale and DIY initiatives.

Scenographic aspects of Boccaccio. Edited excerpts taken from Deville, Jozef. The Sound of Belgium. 2012.

On the other hand, the 90s and the following decades saw a boom of large-scale events and festivals. Sacha Vermeulen's documentary 30 jaar Dutch dance gives a detailed insight in how the African-American underground scene (and the established disco-scene) were imported in The Netherlands. This resulted in infamous clubs as Roxy in Amsterdam, illegal raves, new music genres, the commercialisation and the industry it has become today.8

8. Vermeulen, Sacha. 30 jaar Dutch Dance. 2018.

https://www.vpro.nl/programmas/30jaardutchdance.html

As club culture became mainstream, it also broadened the environments where the events took place. While before, club culture resided in designed clubs, underground locations or community centres in cities, it is rave culture that unfolded it to outside locations and large warehouses in suburban and rural environments. Also, a time-shift occurred sometimes, bringing it from the concealing night to the bright daylight.

Moreover, the DJ took more and more the centre of attention, in some cases taking almost literally the role of a rock star: being staged in the middle of a stadium, behind nothing more than a couple of decks and a mixer. As this situation is visually not pleasing, overwhelming shows on exuberant stages with decors, props, special effects, video screens and tons of light were added. While this could be seen as club culture related scenography as such, a significant shift in roles and functions happens. While we could consider a club as an immersive environment, the situation above adds a very directional way of looking: towards the stage, towards the DJ, the performer of the night. This inevitably directs the light towards the stage as well, literally becoming the brightest spot in the venue. At the same time, the DJ hijacks all the entire environment, claiming all the attention, but also limiting freedom of movement and self-expression, turning the whole event (including the audience) in a choreographed show. This setup and function has much more in common with gigs, concerts or conventional forms of theatre and is also opposite to what Barthes thought was exciting and a new form of art.

It clearly shows how club culture developed into practices that share some of its aesthetics but cannot be considered as club culture anymore. Also, the intent, expectation and behaviour of the audience became very different. How can club culture be still relevant when every kid grows up with these disco-aesthetics and is used to the spectacle of the entertainment industry?

Club culture today

If we compare the aftermovies of two Belgian dance festivals, Tomorrowland and Horst, they both show their power to reunite people from all over the world, turning it into a peaceful celebration of life. However, the way of approaching this and the choice of aesthetics (also in the movie itself) can't be more different.

HORST Arts & Music Festival 2018: A Short Documentary. 2018.

It's interesting to see how Horst reinvents itself every year. The most prominent strategy is to entrust artistic decisions (other than the music programming) to an external pool of artists and architects. Besides creating artistic works and doing interventions, they also design the very core of the festival: the dancefloors (not stages). A community, created by local and international volunteers, executes the design. By doing this, Horst keeps on investigating what club culture is and what the festival and the act of participating means.

Tomorrowland Belgium 2019 : Official Aftermovie, 2019.

While Tomorrowland could be seen as an artistic answer to Foucault's heterotopia, it's probably intended as an entertaining (and money-making) event topped with a fairytale narrative and Disneyesque aesthetics, without any other underlying motivations.

Far more outgoing, fun and exciting than their heteronormative counterparts are queer parties. Moreover, they still play an essential role in these communities, a role that goes beyond aesthetics and entertainment.9 In some parties, we can even discover an urgency to dance. As such, Bogomir Doringer, a visual artist, filmed different clubs from a bird' s-eye view with the aim to document variations of collective and individual choreographies worldwide. In his ongoing PhD research, he defined the term Dance of urgency as a dance that rises in the time of personal and collective crises and that aim to empower individuals and groups. In the exhibition he curated he illustrated this with a range of historical and contemporary documents and artworks where the act of dancing takes a political dimension and where the dance of people reflect the socio-political environment and their struggles.10

9. van Langen, Peter. Last Dance. 2019.

https://kabk.github.io/go-theses-19-peter-vanlangen/

10. exhibition curated by Doringer, Bogomir. Dance of Urgency. frei_raum Q21 exhibition space, Vienna, 2019. https://danceofurgency.com

10. exhibition curated by Doringer, Bogomir. Dance of Urgency. frei_raum Q21 exhibition space, Vienna, 2019. https://danceofurgency.com

Jan Beddegenoodts about his documentaries on display at he Dance of Urgency exhibtion.

While dancing or participating in club culture is most often not political, we see, in the last 5 years, a much more outspoken political stance from party organisers, promoters and crews. It's difficult to prove that this is a reaction to the industry, but it definitely shows that social and political motivations can be far more important than the financial aspects.

Today we should not underestimate the role of the (social) media, making it possible to communicate political motivations and opinions that are difficult to elaborate on at the event itself. Yet, during the parties, they can be expressed in a myriad of non-lexical ways by the organisers and the partygoers. In some circumstances, simply attending a particular party can be a political act, as such.

In the local queer scene, we can recognise that there is more attention going to the minorities within the scene, putting forward the still marginalised groups (trans, non-binary, refugees, etc.) and supporting them in the fight for equal rights, recognition and empathy from society. We can see that these concerns also find their way to the more popular clubs, making feminism, to give an example, not only a topic, but an active strategy translated into their practice.